Introduction: The Concrete Conundrum – Strength and Weakness

Concrete is the undisputed champion of the construction world, the most widely used man-made material on the planet. Its exceptional compressive strength makes it ideal for handling immense crushing loads, forming the foundations, columns, and dams that support our civilization. However, for all its strength, it harbors a critical Achilles’ heel: a very low tensile strength. This fundamental weakness means that while it can bear immense weight, it cracks and fails easily under bending, stretching, or stretching forces. For centuries, this limitation restricted the spans and slenderness of concrete structures, necessitating bulky, heavily reinforced members that were often inefficient and aesthetically limiting.

The ingenious solution to this age-old problem is Prestressed Concrete. This advanced engineering technique is the invisible force behind the vast, graceful spans of modern bridges, the soaring heights of skyscrapers, and the resilient piles that anchor our infrastructure in the ground. It is a technology that allows concrete to perform in ways previously thought impossible. In this comprehensive guide, we will unravel the core principles of prestressing, explore its different methods in detail, highlight its transformative benefits, and examine its pivotal role in modern construction across a multitude of applications.

What is Prestressed Concrete? A Simple Analogy

To understand the core concept, consider a simple analogy. Imagine a row of books you’re trying to carry. If you just hold them from the bottom with your hands, they will sag, buckle, and likely tumble to the floor. However, if you apply firm pressure from the sides—squeezing the entire stack together—you create a cohesive, monolithic unit that is easy to carry and resists sagging.

Prestressed concrete operates on a nearly identical principle. It is a sophisticated concrete construction material that has been pre-compressed in specific regions where tensile (stretching) stresses are known to occur under load. This pre-compression is not a random act but a carefully engineered process achieved using high-strength steel tendons (strands or bars) that are strategically tensioned and anchored against the concrete.

By introducing a controlled, internal state of stress before the actual service loads—such as the weight of vehicles, people, or wind—are applied, engineers can effectively neutralize or drastically reduce the tensile stresses that would cause ordinary, non-prestressed concrete to crack and fail. This process allows us to harness the full potential of concrete’s compressive strength while mitigating its tensile weakness.

The Core Principle: The Science of Induced Compression

The fundamental principle of prestressing is elegantly simple yet profoundly powerful: to counteract anticipated tensile stresses with intentionally induced compressive stresses.

Let’s break this down with a visual example. In a standard reinforced concrete beam supporting a load, the beam bends. This bending places the bottom fibers of the beam in tension. Since concrete’s tensile strength is only about one-tenth of its compressive strength, these bottom fibers crack long before the top fibers reach their crushing limit. The embedded steel reinforcement (“rebar”) then acts to hold the concrete together, but the cracking is inherent and limits the structure’s efficiency and durability.

In a prestressed concrete beam, the high-tensile steel tendons are stretched by powerful hydraulic jacks and anchored. When this tension is released, the tendons desperately want to return to their original, shorter length. However, the concrete, now bonded or anchored to them, holds them back. This internal struggle creates a permanent, state of compressive force within the concrete itself.

When the service load is applied, the resulting tensile stresses are not fighting against weak, un-stressed concrete. Instead, they must first overcome this built-in, beneficial compression before any net tension can develop in the concrete. In a well-designed prestressed member, the concrete section remains entirely in compression under normal use—a state in which it performs exceptionally well and remains uncracked. The high-strength steel, meanwhile, is perfectly suited to handle the immense and permanent tensile forces it carries.

Key Benefits of Prestressing in Construction: Why It’s a Game-Changer

The process of prestressing is more complex and requires higher-quality materials and workmanship than conventional reinforced concrete. So, why is it worth the effort? The advantages of prestressed concrete are so transformative that they have redefined the possibilities of structural engineering:

-

Superior Crack Control and Enhanced Durability: This is arguably the most significant benefit. By preventing significant tensile stress, prestressing virtually eliminates flexural cracking under service loads. This is crucial because cracks provide an open pathway for water, chlorides (from de-icing salts), and carbon dioxide to penetrate the concrete. These elements cause corrosion of the internal steel reinforcement, which is the primary cause of deterioration in concrete structures. By keeping the concrete uncracked, prestressing dramatically enhances the durability of concrete structures, leading to a longer service life and significantly reduced long-term maintenance costs. For more on designing for longevity, see the American Concrete Institute’s resources on durability.

-

Full Section Utilization and Material Efficiency: In conventional reinforced concrete, the concrete in the tension zone is considered cracked and ineffective. It is dead weight that the structure must carry. Prestressing allows the entire cross-section of the concrete to actively resist load. This makes the material use incredibly efficient, leading to reductions in the size of structural members and the amount of concrete and steel required, which also has sustainability benefits.

-

Remarkable Deflection Control: Prestressed members are significantly stiffer and exhibit much smaller deflections (sagging) under the same load compared to their reinforced concrete equivalents. This allows engineers to design shallower, more slender beams and longer spans, creating more elegant, open, and column-free architectural spaces that are highly valued in modern buildings.

-

Ability to Achieve Longer Spans: This is one of the most visible benefits in infrastructure. Prestressing enables the construction of bridges, roofs, and floors with far longer unsupported spans than is possible with ordinary reinforced concrete. This is why you see prestressed concrete I-girders and box girders as the standard for highway bridge construction and overpasses around the world.

-

Improved Shear Resistance: The internal pre-compression also has the beneficial effect of increasing the shear strength of the concrete. This reduces the need for as much conventional shear reinforcement (stirrups), simplifying construction and improving the durability of the member by reducing congestion of steel.

-

Rapid Construction and Industrialization: The use of precast prestressed concrete components allows for off-site fabrication in controlled factory environments. These high-quality elements can be mass-produced and then quickly transported and assembled on-site like a kit of parts, accelerating project timelines significantly and improving quality control—a key factor in modern construction technology.

Methods of Prestressing: Pre-Tensioning vs. Post-Tensioning

There are two primary, distinct techniques for introducing prestress into concrete, each with its own specific processes, advantages, and applications.

1. Pre-Tensioning

In pre-tensioning, the steel tendons are tensioned before the concrete is cast. This is primarily a factory-based process.

-

The Detailed Process:

-

Bed Preparation: High-strength steel strands are laid out along a long, strong “pre-tensioning bed” between two robust abutments that are firmly anchored to the ground.

-

Tensioning: Using high-power hydraulic jacks, the strands are stretched to a predetermined stress level, typically around 70-80% of their ultimate tensile strength.

-

Casting: With the strands held in this stretched state, concrete is poured into molds surrounding the tensioned strands.

-

Curing: The concrete is allowed to cure and gain sufficient strength, often accelerated by steam curing to improve production efficiency.

-

Detensioning: Once the concrete reaches the required strength (usually 75% of its 28-day strength), the strands are carefully released from the abutments. As the strands try to elastically shorten, they transfer their stress to the concrete through bond and friction along their length, inducing the vital compressive force.

-

-

Applications: Pre-tensioning is predominantly used in the high-volume, mass production of standardized, repetitive components. Common examples include:

- Precast concrete beams and lintels

- Hollow-core slabs for floor and roof systems

- Double-T and Single-T sections for long-span decks

- Railway sleepers (ties)

- Paving slabs and concrete piles

2. Post-Tensioning

In post-tensioning, the steel tendons are tensioned after the concrete has hardened and gained strength. This method is highly versatile and can be used both in precast plants and for cast-in-place structures on-site.

-

The Detailed Process:

-

Duct Placement: Corrugated steel or plastic ducts (sheaths) are placed in the formwork in the exact profile where the tendon will run.

-

Casting: Concrete is poured and vibrated, carefully leaving the ducts empty and unobstructed.

-

Curing: The concrete is allowed to harden and gain strength.

-

Threading and Tensioning: After the concrete is strong, the high-strength steel tendons (which can be single bars, multi-wire strands, or bundled strands) are threaded through the ducts.

-

Anchoring: Using specialized hydraulic jacks, the tendons are tensioned from one or both ends and anchored using permanent, cast steel anchorages that bear against the concrete surface.

-

Grouting (in bonded systems): For most applications, the empty ducts are then pressure-filled with a cementitious grout. This serves two critical purposes: it bonds the tendon to the concrete, creating a composite section, and it protects the high-strength steel from corrosion.

-

-

Applications: Post-tensioning is the go-to method for large, custom, and complex structures. Its applications are vast:

-

Bridge construction (segmental box girder bridges, balanced cantilever bridges)

-

Post-tensioned slabs in high-rise buildings and parking garages, allowing for thinner slabs and wider column spacing.

-

Nuclear containment vessels and other critical safety structures.

-

Heavy-loaded transfer girders that support columns above.

-

Slabs-on-ground for industrial warehouses to control cracking and eliminate contraction joints.

-

The Post-Tensioning Institute (PTI) provides extensive guidelines, design manuals, and resources on this method.

A Deeper Dive: Materials Matter – The Backbone of Prestressing

The effectiveness of prestressing hinges on the use of advanced materials that can withstand immense forces.

-

High-Strength Steel: The tendons are not ordinary rebar. They are typically made from:

-

High-Tensile Steel Strands (7-wire strand): This is the most common tendon, consisting of six wires spiraled around a central wire. It has a typical ultimate tensile strength of 1860 MPa or 270 ksi, which is about three times stronger than standard rebar.

-

Stress-Relieved Strand: The strand is heat-treated to reduce relaxation (the loss of stress under constant strain).

-

Low-Relaxation Strand: The modern standard, it undergoes a special thermal-mechanical treatment to exhibit very low stress loss over time, making designs more efficient and predictable.

-

-

High-Performance Concrete:

The concrete used must be strong enough to withstand the high bearing stresses from the anchorages and the intense pre-compression. It typically has a compressive strength in the range of 35 MPa (5000 psi) to over 70 MPa (10,000 psi). It also requires excellent workability to be placed around congested tendon ducts and high durability properties to ensure a long service life.

Applications of Prestressed Concrete: Shaping the Modern Landscape

The impact of prestressing is all around us, forming the skeleton of our modern infrastructure. Key applications of prestressed concrete include:

-

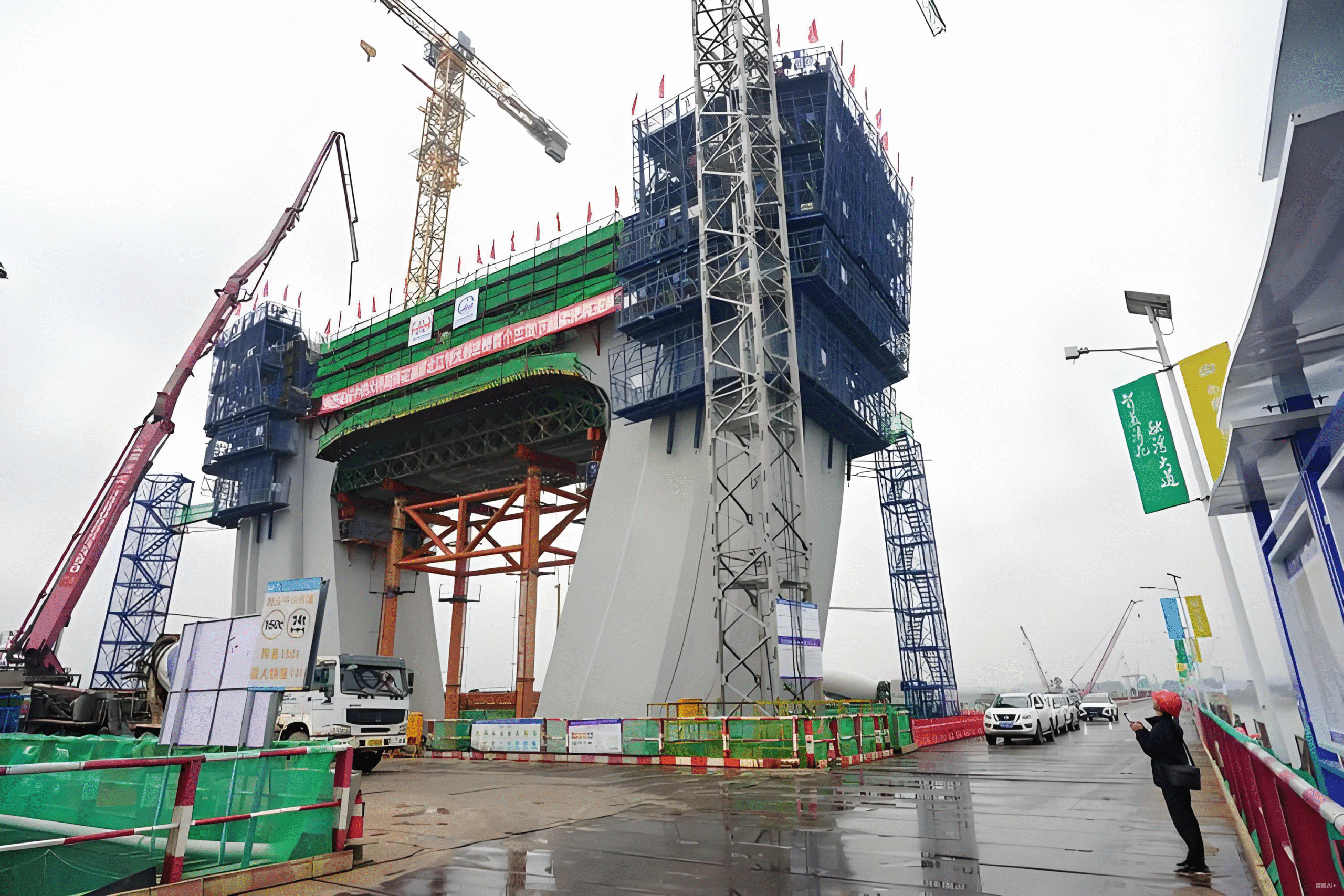

Bridges: This is the flagship application. From the massive pre-tensioned girders of highway viaducts to the elegantly complex segments of post-tensioned cable-stayed bridges, prestressing is the backbone of modern bridge engineering. It allows for longer spans, fewer piers in difficult terrain or waterways, and more durable decks resistant to de-icing salts.

-

Building Structures: In commercial and residential construction, it is used in:

-

Long-Span Floor Systems: Hollow-core slabs and post-tensioned flat slabs create large, column-free spaces in offices, auditoriums, and hospitals.

-

Parking Structures: The combination of durability against salt and the ability to create long spans and sloped ramps makes prestressed concrete ideal for parking garages.

-

-

Water Retaining Structures: Prestressing is ideal for circular water tanks and reservoirs as the hoop tension is perfectly counteracted by circumferential prestressing, preventing cracking and ensuring watertightness.

-

Marine Structures: Its superior durability against the harsh saline environment makes it perfect for piles, offshore platforms, docks, and seawalls.

-

Special Structures: It is critical for silos (resisting hoop tension from stored materials), nuclear reactor containment vessels (providing leak-tight integrity), and other heavily loaded industrial structures.

Challenges, Considerations, and the Management of Prestress Losses

While immensely beneficial, prestressing is not without its challenges. It requires high-quality materials, highly skilled labor, and rigorous quality control throughout the process. The consequences of failure, such as tendon corrosion due to improper grouting or anchorage failure, can be severe and catastrophic. Therefore, proper design, meticulous supervision, and experienced contractors are paramount.

A critical aspect of design is understanding and accurately accounting for prestress losses. The initial force applied to the tendon is not the force that remains in the structure for its entire life. Several time-dependent factors cause a reduction in this force:

-

Elastic Shortening: As the concrete is compressed, it shortens elastically, slightly reducing the tendon stress.

-

Creep of Concrete: Under sustained compression, concrete continues to slowly deform over time, further relaxing the tendon.

-

Shrinkage of Concrete: As concrete cures and dries, it shrinks. This shortening also reduces the prestressing force.

-

Steel Relaxation: The high-strength steel itself, under constant high stress, undergoes a slight, time-dependent loss of stress.

Engineers must carefully estimate these losses and apply an initial prestressing force that is high enough to ensure that, after all losses, the final prestress level is still adequate for the structure’s lifetime.

Conclusion: The Future is Prestressed and Evolving

Prestressed concrete is far more than just a construction material; it is a foundational technology of modern civil engineering. By cleverly and robustly overcoming concrete’s inherent weakness in tension, it has unlocked new horizons of strength, durability, and architectural expression. From the efficient precast concrete elements that speed up our construction projects to the monumental post-tensioned bridges that connect our cities, the principles of prestressing continue to shape a stronger, more resilient, and more ambitious built environment.

As we look to the future, the evolution of prestressed concrete continues. We are pushing the boundaries with:

-

Advanced Materials: The development of Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC), with compressive strengths exceeding 150 MPa and significant inherent tensile ductility, is creating even stronger, lighter, and more durable prestressed members.

-

Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (FRP) Tendons: As a non-corrosive alternative to steel, FRP tendons (made from carbon or glass fibers) are being researched and deployed in highly aggressive environments, promising an even longer lifespan.

-

Digitalization and BIM: Building Information Modeling (BIM) allows for the precise digital fabrication and placement of complex post-tensioning layouts, reducing errors and optimizing construction sequencing.

The fundamental concept of prestressing—using pre-emptive force to enhance performance—will undoubtedly remain at the forefront of innovative construction technology for generations to come, enabling us to build higher, longer, and smarter than ever before.